By Michael V. Cusenza

Mayor Eric Adams on Thursday launched an admittedly ambitious effort to tackle the City’s persistent and severe housing shortage and enduring affordability crisis by enabling the creation of “a little more housing in every neighborhood.”

As the lack of available homes drives up rents and pushes more New Yorkers into the shelter system, Adams boasted that his “City of Yes for Housing Opportunity” proposal would help the New Yorkers who have built the Big Apple afford to stay here by creating an additional 100,000 homes — enough to support more than 250,000 New Yorkers — over 15 years and more than 250,000 family-sustaining jobs. Additionally, Adams said, the plan would provide $58.2 billion in economic impact to the city over the next 30 years.

The steps Adams proposed on Thursday would be the most significant pro-housing reforms ever to the City’s baroque zoning code and a step towards his “moonshot” goal of delivering 500,000 new homes to New Yorkers over the next decade.

The new initiative represents the third of three citywide zoning changes that will be presented to all five borough presidents, all 59 community boards, and the City Council as part of Adams’ vision for Gotham as an inclusive, equitable “City of Yes.” As the majority of New Yorkers spend more than one-third of their income on rent, and fewer than 1 percent of apartments listed under $1,500 monthly rent are available for new tenants, the City of Yes for Housing Opportunity marks the first time a mayoral administration has proposed unlocking more housing on a citywide basis — offering a roadmap for every community to do its part to address this citywide crisis, Adams said.

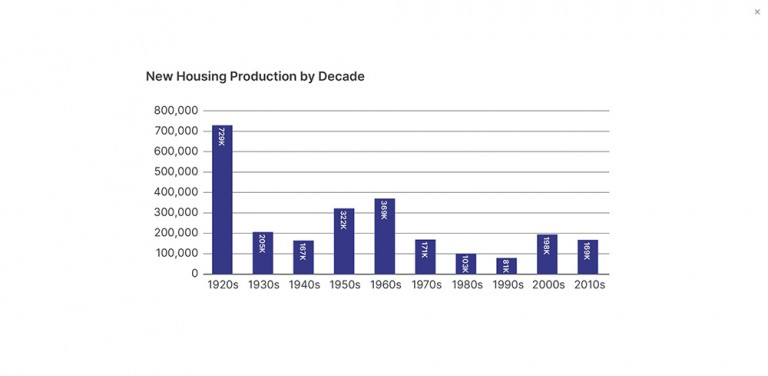

For decades, increasingly complex and restrictive zoning has impeded the creation of new housing and magnified inequities among communities across the city, with just a few neighborhoods producing the majority of the city’s new homes and some neighborhoods even losing homes overall, Adams said. New housing production has slowed to a crawl — from an average of nearly 37,000 new homes approved every year in the 1960s to barely 8,000 annually in the 1990s and, most recently, approximately 20,000 homes approved each year in the 2010s. The proposed zoning changes in the City of Yes for Housing Opportunity will reverse those trends and unlock much-needed new housing in every neighborhood across the city, Adams crowed on Thursday.

Highlights of Hizzoner’s historic housing proposal include:

Ending Parking Mandates for New Housing

Across much of New York City, decades-old regulations require certain fixed numbers of parking spaces to be built alongside new homes — driving up costs and ultimately blocking housing by making many projects infeasible. These government mandates add an estimated $67,500 per underground parking space in construction costs and require valuable space to be reserved for cars instead of additional homes for New Yorkers.

This proposal will eliminate requirements that new homes come with new parking spots. Parking would not be barred from new developments, but this plan would get zoning regulations out of the way so developers could make decisions consistent with the market and their potential residents.

Universal Affordability Preference

The Universal Affordability Preference policy would bring permanently affordable homes to neighborhoods citywide. Building on the successful Affordable Independent Residence for Seniors program — which allows affordable senior housing to be about 20 percent larger than other types of housing — this policy would extend that preference to all types of affordable housing. Had Universal Affordability Preference been in place since 2014, New Yorkers could have benefitted from an additional 20,000 income-restricted homes where an additional 20,000 city families would be guaranteed to spend no more than 30 percent of their income on rent.

Shared Living

Around the world, cities have lowered housing costs by allowing modest apartments where residents share some common facilities, like kitchens and bathrooms, the mayor noted. New York was once full of options like these — but, over time, regulations have made this kind of housing all but impossible to offer. This proposal would adjust current rules that mandate larger unit sizes, allow more smaller-sized apartments to reduce the need for single adults to live with roommates, and re-legalize homes with shared kitchen or bathroom facilities while maintaining strong building code and livability standards.

Town Center “Main Streets” Zoning

Increasingly restrictive zoning has made it illegal to construct the kinds of commercial corridors that make neighborhoods across New York City vibrant and distinct. Along these corridors, the “town centers,” or “Main Streets” of respective communities, this proposal would allow between two and four stories of residential development over ground-floor commercial space to encourage mixed-use communities and foster naturally affordable types of housing.

Transit-Oriented Development

Connecting new housing to accessible public transportation can ease congestion, cut harmful carbon emissions, and reduce car ownership — fostering a safer, cleaner, and more prosperous city. But in many parts of New York, current zoning forbids even modest apartment buildings. This proposal would allow apartment buildings between three and five stories on large lots near transit stops in places where they will blend with the existing neighborhood. These small multifamily buildings are already a part of New York’s fabric — making up more than one in five homes in one- and two-family neighborhoods — but have been banned by increasingly restrictive zoning in recent decades.

Accessory Dwelling Units

Backyard cottages, garage conversions, and basement units have delivered enormous benefits to homeowners across the country — allowing seniors struggling to stay in their neighborhood on a fixed income or young people stretching to afford a first home a way to earn extra income. This proposal would legalize an additional dwelling unit of up to 800 square feet on one- and two-family properties across the five boroughs, adding new housing that fits into neighborhoods, while providing space for multigenerational families, health aides, or local workers.

Converting Empty Offices into Housing

Turning vacant commercial space into homes offers a win-win for New Yorkers looking for new homes and the city’s economic recovery — creating housing more efficiently in already-existing buildings, while maximizing use of otherwise-underused space and enlivening neighborhoods, Adams said. Today, arbitrary restrictions dictate that depending on the year a building was constructed, conversion may or may not be possible. Thursday’s proposal would update the year of construction to 1990 for flexible conversion regulations, extend geographic eligibility to anywhere in the city that zoning permits housing, and allow conversion to more types of homes, including supportive housing. Through these changes, commercial space could be converted to create an additional 20,000 homes over the next decade.

Maximizing Campuses

Large campuses across the city have underused space that could be used to house New Yorkers. The creation of new homes could fund repairs to existing buildings, revitalize institutions, and help address the city’s housing crisis. But complex and outdated rules stop campuses from adding new buildings if, for example, an older building is above a height limit — even if the older building is allowed under the rules in place when it was built. This proposal would ease approvals for new buildings on campuses that reflect the context of the surrounding buildings — allowing properties ranging from multi-building housing developments to religious institutions to create new housing and support the revitalization of their communities.

Today, we are proposing the most pro-housing changes in the history of New York City’s zoning code — changes that will remove longstanding barriers to opportunity, finally end exclusionary zoning, cut red tape, and transform our city from the ground up,” Adams added.