One writer had a simple request: for women to be able to drive cars, taxis and buses. Another wrote about how she felt she had lost her freedom once she hit adolescence. And another told of her struggles of wearing a burqa: she believed if she did not wear it, she would be stoned.

Queens residents gathered Monday at the Richmond Hill library to hear the firsthand accounts of life in Afghanistan by women who live there.

Friends of the Richmond Hill Library hosted guests from the Afghan Women’s Writing Project, an organization through which American writers mentor aspiring women writers from the Middle Eastern country. The writers’ work is published by the AWWP in its online magazine.

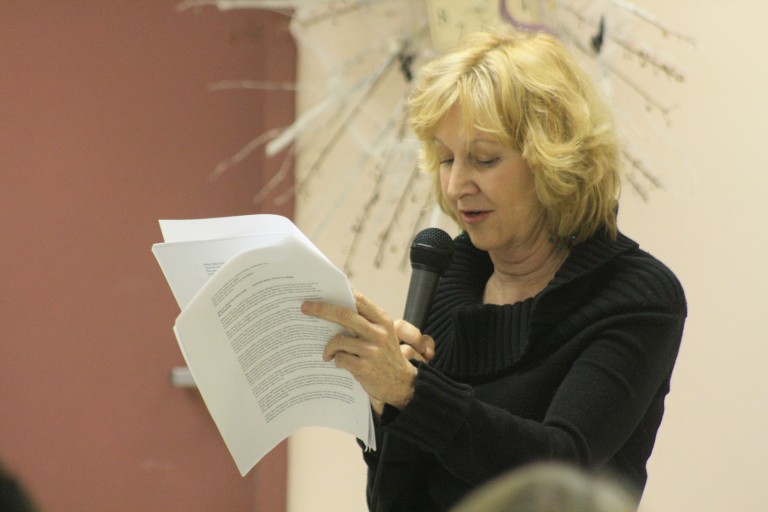

Masha Hamilton, the founder of the Afghan Women’s Writing Project, reads from her work at the Richmond Hill library. Photo by Bianca Fortis

The essays and poems were read by guests from Afghanistan, as well as AWWP staff members and audience volunteers.

Some of the writers use their words to describe their dreams and goals in life. One was a conversation with God; it asked, “God, if you were an Afghan woman, would you be sorry?”

Other stories are more graphic: one writer told the story of a 24-year-old woman named Tahera, who was starved, beaten and burned alive by her family members after she had been seen riding on a motorcycle with a boy.

The event featured novelist and AWWP founder Masha Hamilton, who read a passage from her most recently published book, “What Changes Everything,” part of which is set in Afghanistan.

Hamilton previously worked in Afghanistan as the director of communications and public diplomacy at the U.S. Embassy.

She said some women choose to write about violence, the Taliban, and the American occupation of their country. Many others, though, write about the marginalization of women and the struggles they face in their own lives.

“By and large they tend to write about what is most personal and closest to them,” she said.

Hamilton, a former journalist, was inspired to start the organization as a tribute to a woman named Zarmeena, who was executed by the Taliban in a stadium in 1999. Initially, Hamilton taught an online writing course as a personal dedication to Zarmeena, but soon saw how meaningful the class was for her students. She reached out to other published authors and friends and formed the mentorship program.

Since April 2010, AWWP has published more than 900 poems and essays by more than 170 Afghan writers. In 2012 the organization opened a women-only internet cafe in Kabul at which participants can practice their trade.

Hamilton said the front of the cafe is not marked, in order to protect the women’s safety, but that the AWWP is “pretty well known in Kabul.”

She said of the Afghan writers keep their writing a secret either because their relatives are opposed to their participation in the project or because family members worry for the women’s safety. One writer, who would make the trek from her home by foot to submit her poems, was killed in an explosion, Hamilton said.

But other family members are proud.

“There are men and fathers who are extremely supportive,” Hamilton said. “We do have men who know their daughters are writing and they think it’s great.”

“I’d like to say we’ve reached a tipping point for women [in urban areas], but not in the villages,” she continued.

For more information about the Friends of the Richmond Hill library as well as its book readings, visit http://www.richmondhillny.com/library/frhl.html

For more information about the Afghan Women’s Writing Project, visit awwproject.org.

By Bianca Fortis